The opinions provided by contributors are not endorsed by Trackforce Valiant + TrackTik. This piece’s purpose is to provide various viewpoints from thought leaders in the physical security space on recent articles published by Time Magazine.

Jeff DiDomenico

Vice President, Business Development and Strategy

Trackforce Valiant + TrackTik

Security industry veteran Jeff DiDomenico lends his and other security industry experts perspective on recent media coverage of the security industry.

Perhaps you’ve read the three-part series titled “INSECURE, The Explosive Growth In The Private Security Industry Since 2020,” by Alana Semuels, a Senior Economics Correspondent at Time Magazine.

If you haven’t, I encourage you to seek out the series of articles. If you have, your initial reaction as a physical security industry professional was most likely like mine. That this is another one-sided, anecdotal article filled with inaccuracies and leading with exaggerations. But there are also some accuracies within.

So how do we respond? What actions do we take?

We know the industry. We know that it’s not easy to be in the trenches every day. But we also see the individual workforce, we understand the challenges, and we know the everyday successes. Together, we can work even harder to improve our industry.

First, let’s pause and collectively appreciate the excellent work that private security officers do each day at physical security firms. We applaud their efforts in every situation, including difficult and unprecedented global crises such as COVID-19, where front-line security officers played pivotal roles in changing playbooks due to the situation that we all faced.

Let’s also take the opportunity to appreciate the physical security industry leaders who have guided those security officer teams through all tough times. There are so many to recognize but thank you to all of you.

Second, let’s recognize that security guards aren’t perfect. They’re human like all of us, and they may make mistakes. Focusing solely on their faults and flaws is unbalanced and a disservice to public safety.

Third, some of what is painful to hear in this article is because it’s true. Like many in the industry, we do agree with the calls for higher pay, standardized regulation, background checks, an investment in technology, proper training, and more. And as advocates of the industry, this is what leads me to my final point.

Fourth, I view this as a “call to action,” as an opportunity to face some of the painful but justified criticism that is the physical security industry. I did what I always do: I reached out to our industry’s veteran leadership, owners, and service providers.

Inclusive in this posting are over 140 years of dedication, commitment, and stewardship to an industry that is often overlooked. Industry leader comments, thoughts, ideas, and call to action are listed here.

Individually, please consider joining your local ASIS Chapter, SIA MD, or your state-run association – ASSIST of Texas, CALSAGA of California, ISPA of IL, or FASCO of FL so that, through legislation and other initiatives, recruiting, education, and training are both affordable and accessible. They are helping to further our industry. Additionally, we can contact our local government representatives and share our stories, concerns, and goals. We can place the correct message in front of them.

Friends, let’s take this opportunity to act, create change, and move our industry forward. Even with all of the criticism, one thing remains clear: that the physical security industry is here to stay, and remains important in keeping the general public safe.

We hope this serves as a reminder for regulators, clients, private security companies, and the general public that the work isn’t over. In fact, it has only just begun.

Jeff DiDomenico

Vice President, Business Development and Strategy

Trackforce Valiant + TrackTik

Read through the responses of our esteemed industry leaders

“Bad news sells magazines. Good news? Not so much.”

Written by: Robert H. Perry, President & CEO

Robert H. Perry & Associates, Incorporated

“When we see critical headlines, we dig in to read what some zealous reporter has uncovered, whether it be about a politician that’s been accused of sexual harassment or otherwise breaching the duties of his/her elected position or some CEO of a public company that’s been investigated for breaching his fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders. Unfortunately, this also applies to the security guard industry that’s been under fire from the press lately, the most recent being the scathing articles published by a national newspaper and a well-known and respected magazine

There have been several critical headlines in the past that conjure up juicy reading. Some that come to mind are articles with tag lines such as: “Who’s Guarding the Guard” and “Do Policemen Make Good Security Guards?” We all remember the saga of Richard Jewell, the security guard working at the Atlanta Summer Olympics in 1996.

At first, he was called a hero for discovering the bombs, then he was accused of planting the bombs and this news hit the front page for several days. He was later cleared, but not before there was a lot of character assassination aimed at Mr. Jewell and the entire security guard industry.

By the way, there was never an apology to Mr. Jewell for the false accusations, who died soon after he was cleared. Some say his death was the result of the stress coming from the bad publicity – but some of the scars the security guard industry got from this unfortunate series of events still remain.

And of course, there’s always the “Mall Cop” movie that is still referred to today as a way to downgrade the security guard industry. Even though these articles bring heightened anger to the many fine professionals in the security guard industry, it is interesting reading to the general public and as long as readers line the pockets of these media companies, these articles probably won’t stop anytime soon.

The very unfortunate part is that the general public, after reading the articles, develops a biased perception that the isolated incidents being reported on holds true for the industry as a whole. Sure, some of these companies have had bad hires and rogue guards, but the isolated incidents are minuscule compared to all the positive contributions the security guard companies make in protecting our country, its citizens, and assets.

It’s evident that most of the incidents the reporters mention in their articles are derived from talking with a very small sample of disgruntled guards or reading isolated events that are often retracted but show up on the “back page.” If reporters wanted a more accurate picture of the industry, which probably wouldn’t be as exciting – thus wouldn’t sell as much copy – they should draw from a larger sample of the approximately 8,000 professionally-run companies making up the U.S. manned guarding industry.

But I’m not sure all the blame for the somewhat aggressive and underserved critical reporting should fall entirely on the shoulders of the zealous reporter. The problem the reporters have in getting this greater sample is that the owners would not take the reporter’s call.

We found many years ago that the security industry is made up of owners that are by nature secretive. They are concerned that their success and proprietary management, no matter how beneficial to the industry, will fall into the hands of some of their competitors. Therefore, they’re very careful and selective as to who they talk with and how much information they are willing to share, if any.

Our firm had to start many years ago gaining the trust of the owners of security guard companies that would eventually give us the information we needed to publish a comprehensive annual white paper on the industry, now coming up on its 15th edition. They gave us the information we needed in exchange for our promise to use the information without mentioning their names in our report.

- We found out a lot about how professionally run these companies are and the contributions they are making such as:

- The companies are licensed in the states in which they operate.

- Most not only adhere to the training requirements of that state but usually exceed them.

- Most require a psychological test when hiring a guard that matches the guard’s personality traits to the particular post to which the guard will be assigned.

- Most are making large investments in technology or artificial intelligence to upgrade service delivery.

- All are asking the customers for billing increases and passing the increases on to the guards. Most are still left with a lesser margin, as before the labor shortage, due to not getting as much billing increase as needed to offset the higher cost of labor.

- Most are upgrading the accounting and payroll functions to ensure the guards are paid on time. And some are paying their guards faster to enhance the recruiting process.

- Many are replacing the municipal police force. The private security company has, in a lot of instances, better training and a better career path for the management staff.

Obviously, these characteristics do not make for exciting copy. They wouldn’t bring in big bucks to the publishers. We’ll probably never see an article on the manned guarding security industry that even comes close to giving the industry the credit it deserves.”

“It’s time for the industry to gain a centralized voice.”

Written by: Jack Goldsborough, Principal

Whitehaven Advisors LLC

“The 3-part series “Insecure” on the private security industry by Time author Alana Semuels is the latest media hit piece on the shortcomings of the contract guard business. With a seemingly endless collection of anecdotal evidence – albeit some or arguably most of which deserve criticism – Semuels seems to be challenging the industry to take the bait – knowing well that any attempted rebuttal falls flat.

However, this series also correctly reaffirms the growing demand for private security to fill the widening gap between rising U. S. crime and its threats to businesses and personal safety at the same time police force levels and response times are severely constrained. So, instead of a rebuttal, now should be the time for the industry to step up, address these issues and demonstrate its commitment and ability to competently meet this demand.

While Allied Universal’s CEO, Steve Jones, made some worthy points on the valuable role and positive contributions security guards make on a daily basis, he chose not to go further. Historically, the readers of these provocative media articles are rarely provided with a needed and coherent explanation or response from the industry to explain the underlying issues raised such as its continuing and ongoing efforts for corrective legislation and regulatory solutions.

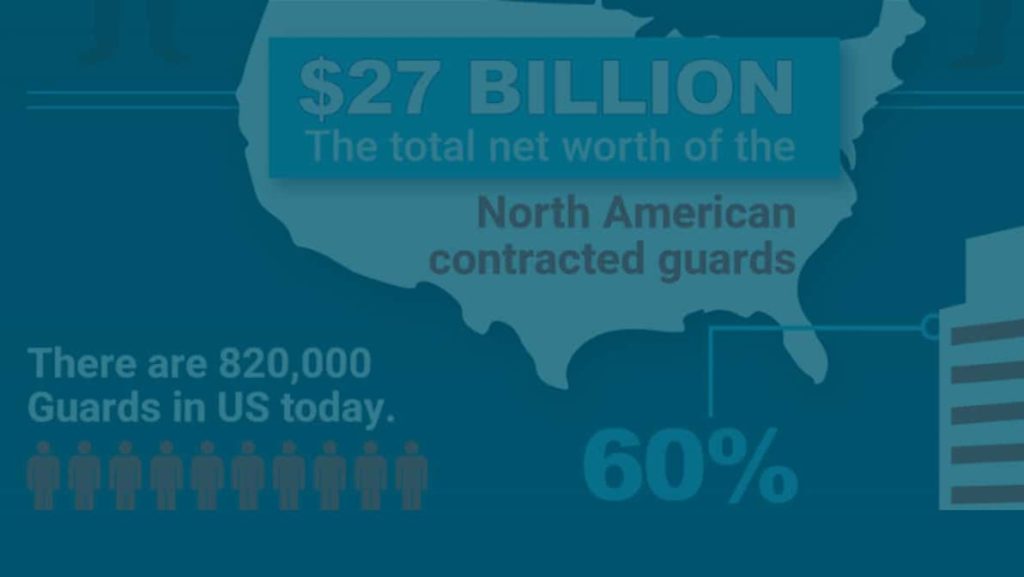

With over 8,000 security companies, this $30B industry lacks a singularly powerful voice for addressing the underlying issues for improving standards and professionalism. So where is its response?

Without a unified collective voice, the industry’s disparate membership associations such as NASCO, and important state associations such as Calsaga, ASSIST, or ISPA lack a sufficiently loud enough megaphone or media response. Hence it is unable to affect any significant influence on meaningful legislation for improving the standards and professionalism of this $30 billion industry.

Nevertheless, NASCO’s contribution and efforts in this area are noteworthy and deserve recognition, as does its well-stated mission:

“To promote public awareness of the important role of private security in the United States and the valuable services provided by private security companies and their officers across the country. To shape and inform governmental and public policies and perceptions concerning private security. To advocate at the federal, state, and local levels on behalf of private security firms and on the licensing, screening, and training of private security officers.”

However, it should be realized that NASCO’s actual responsibility is representing only the constituent interests of its members (actually just 18 firms including Allied Universal) – and not the rest of the 8,000 estimated security guard and patrol companies in the U.S. market. Thus, lacking significant influence and effective lobbying clout ($$$), the industry as a whole continues to suffer the imposition of adverse employment laws and regulations. Without collective power, such legislation directly hampers industry economics and the ability to provide the quality and higher level of protective services needed to meet these current challenges and growing market opportunities.

One possible solution could be organizing a much broader collective voice. To be effective, this would require an industry consortium encompassing the 8,000+ security companies either through the expansion of NASCO or a similar membership structure across a regional and local network. Such an organization seems essential for gaining the widespread participation and economics of the industry at large to power more effective legislation in support of higher industry standards.

The objective of such an initiative could finally address the ‘Achilles heel’ of the industry – creating a legitimately equal and level playing field where enforceable compliance standards in licensing, qualifications, and training would result in higher market-driven minimum compensation levels.

Why is this necessary? The unspoken problem has been that, without enforceable/mandated standards, users of contract security services – including sophisticated corporate/F500 buyers – of necessity have been compensating for this vulnerability by creating their own criteria and standards of contractual performance in their Requests for Proposal (RFPs).

These contract terms and conditions include full insulation from liability exposure with strong insurance provisions and tight hold-harmless and indemnification clauses. With these protections, buyers know that some of the bidders will risk exposure to contractual liability and even licensing violations by submitting competitive bids that represent themselves as fully compliant with such specs and requirements when they clearly aren’t.

As a result, from that perspective, some buyers force low pricing because they can – as they know there are always some security contractors willing to accept these downside risks to gain recurring contract revenues. Consequently, many well-qualified contractors cognizant of this practice will refrain from participating in RFPs where they know the client organization will not challenge or scrutinize the bidder’s qualifications because they’ll use their RFP and contractual protections as cover for selecting the lowest bidder.

Absent any significant changes or enforcement resulting in a level playing field, these practices will inevitably continue resulting in similar episodes as described in the articles by Ms. Semuels. Hopefully, influential industry leaders and owners will recognize this series of articles as a valuable clarion call to action: particularly the need to address these vulnerabilities and mobilize and fund an industry-sponsored organization action plan.

This plan should have two primary goals:

- Develop and promote realistic and enforceable standards for federal, state, and local legislation and regulations

- Develop meaningful self-regulation for re-establishing and building an improved nationally recognized image and brand representing the professionalism and commitment of the entire contract guard industry.

Otherwise, the only alternative is to wait for the next series of similar articles.

P.S. In the meantime, one proven pathway and business solution is already available and deserves more attention: hybrid or managed services – the effective deployment of [reduced] manned guarding with enhanced technology services.

How does this help? Replacing a portion of reduced manned coverage with higher-margined technologies creates the opportunity with bundled pricing and economic savings to enable the re-engineering and elevation of the security guard/officer role from the traditional passive ‘observe and report’ to a higher and more functionally-effective and valuable role – in some cases as a first responder requiring increased experience, qualifications, and training – requiring commensurately higher pay and benefits.”

“We must closely question unsupported statements.”

Written by: Robert McCrie, Ph.D., Professor of Security Management, CPP, Department of Security, Fire and Emergency Management

John Jay College Of Criminal Justice

Just over 13 years ago (03/09/92), Time Magazine’s Richard Behar wrote a “Special Report: Thugs in Uniform.” The article shook up the security guard industry in this country. It detailed how a few security guards — the thugs in the article — committed criminal acts. Their employers had their eyes on the bottom line, not quality services for their customers, according to the author. I was quoted in the article saying, “There’s a steady stream of horror stories.”

Now Time’s Alana Semuels offers a new three-part series on the industry, “INSECURE,” about the industry since 2020. That term, insecure, serves as a judgment of the entire security guard industry. Again, the industry has been shocked by the assertions in the series. Has the industry learned nothing over these years?

Semuels makes three sweeping charges, one in each article: First, private security guards are replacing sworn police officers. Next, the industry doesn’t have “many rules or regulations.” Finally, the writer picks on the largest security company, Allied Universal, as an exemplar of haphazard management from a company that has grown rapidly and become too unwieldy to do its job well.

As a security educator and writer for over 50 years, I read the articles closely. I respond:

First, are private security officers replacing public police? The answer is positively no. Employment of private security guards has trended up for over a century, but not to replace police. Contract security officers mostly protect the private sector and not-for-profit organizations. Security guard company owners and operators hate the term “private police.” Guards are not selected, trained, and supervised to be police officers. They are expected to detect, deny, delay, respond, and report on emergencies and untoward incidents. Their very presence makes the public feel safer every day.

An exception may be mentioned: law enforcement or other governmental organizations may use private security to protect public buildings and crime scenes so highly trained police officers can be delegated for more urgent tasks. This doesn’t happen often, but it’s a reasonable option.

Next, Semuels argues that the security guard industry has too little regulation and not enough training. I partially agree. Still, progress is occurring. In 1998, only 39% of the states plus DC required a background check, 16% required training for unarmed guards, and only 6% required armed guard training. By 2017, those three measurements had grown to 96%, 64%, and 80% respectively. And now every state and DC has at least some security regulations on the books.

But security guards need more training, especially pre-assignment, and clients should be smart enough to pay for it. (Actually, many do now and have done so for years.) Only eight hours of pre-assignment training is required in many states, including my own. Really? Do you think that’s enough? Barbers require 288 hours of training before they are on their own (cosmetologists need 1,000 hours). The person who could save your life needs more than eight hours of prep time.

Finally, the Time writer provides a list of complaints against Allied Universal, the largest contract security guard company in the country, and an amazing American success story. In 1998, Steve Jones and a partner became involved with a West Coast guard company boasting annual revenues of $12 million. An amazing string of acquisitions and internal growth, aided by exceptional support from equity partners, has grown the company to about 350,000 employees and revenues approaching $11 billion.

Any business that grows that fast makes mistakes along the way, and Allied Universal’s competitors can and should pounce on them. Such mega-employers are likely to have a few employees somewhere who have committed unacceptable acts, including criminal ones. Still, the company reports that its customer retention rate is 10 years and it protects more than 400 of the FORTUNE 500 companies.

As a major source for the articles, Time writer Alana Semuels turned to Rick McCann, founder and CEO of Private Officer International, “an association for security and law enforcement professionals.” McCann is the only source listed in all three articles. I looked closely at some of his attributions. My comments are in italics following his statements:

Pennsylvania and “about 30 other states allow people to get trained as private police officers, which gives them full arrest authority on the private properties where they were arrested.” Not true. Unless they are trained as special police officers in states where such a category exists, private security officers have citizens’ arrest powers, not more.

McCann says that “in the past decade, 309 security officers have been arrested for manslaughter or murder while on duty.” That would be an average of 30-31 per year. I cannot find any valid source for this assertion. About 5% of contract security guards are armed. How are all these crimes supposedly occurring while on the job?

McCann estimates “that there are 13,000 assaults on security guards annually.” Security generally is a safe vocation. While every life is precious and every death regrettable, from 2009-2018, an average of 25.4 homicides of security officers occurred each year with many of these involved with the handling of cash, jewelry, and other fungible assets. McCann’s estimate of assaults might be correct, though the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and Justice Statistics do not break out security guards as a separate category.

I had never heard of Rick McCann or Private Officer International before the articles were published, so I decided to check their websites and learn more. I found serious factual errors and unsupported statements in their postings. I will mention only three:

“[A}t least 279 security officers” died in the attacks of 9/11, according to an email from McCann’s group, IFOP. The number was much lower. One year after the attack, the Associated Licensed Detectives of New York State identified 24 security officers who died that day. Some proprietary security guards might not be counted.

So far this year, 30 security officers have been killed on duty and 68 shot, according to McCann’s statement of May 8, 2023. All workplace deaths and injuries must be reported to the US Department of Labor’s OSHA. The data for 2023 will not be available for a long time, but this figure has no basis except what McCann says. If he has a researchable database of these names and events and posts it regularly, that would be a valuable service. But he can’t just cite numbers like these without some way of verifying them.

McCann is cited as having a master’s degree in criminal justice from North Hills College, 1994-97. North Hills College is not listed among the more than 4,750 colleges and universities listed by BRB Publications in their national directory. This intuition also cannot be verified from a Google search.

Rick McCann calls for higher regulations for security guard companies and for more guard training. I do too. But unsupported statements by him on behalf of his organization and sensationalist reporting by Time need to be closely questioned.